jargon alert – if you don’t work with SaaS companies, I didn’t write this for you. Sorry.

I have a secret for you. Your LTV/CAC ratio isn’t your North Star. Why? Because your LTV/CAC number is a summary statistic. It includes backward assumptions and forward-looking estimates.

But it’s also incomplete.

- By itself, it doesn’t tell you anything about the variance across your customers.

- By itself, it can’t help you set your priorities for the upcoming quarter.

- By itself, it can’t identify areas where you need improvement.

- By itself, it can’t help you justify where to spend new money on people, distribution channels, or internal technology.

- And by itself, it isn’t telling you anything about the future.

And the only thing that truly matters is the future.

This may sound familiar

The question from the Board always appears, as predictably as the sun rises in the east. “What are your unit economics looking like?” And you are prepared — you have your LTV/CAC number in your hip pocket (or on slide 13 of the deck).

“Great,” you say. “At the end of the quarter, our ARR is approaching $5 million. Our LTV/CAC ratio is exactly 3, so we feel great about where we are going. Full steam ahead.”

ASIDE: I’m sure you are a bit more thoughtful and you are talking a great deal about other things like logo and net dollar retention. You are talking about sales cycle and pipeline health. And of course, you are talking about cash burn and runway. But I want to help you protect you from the temptation of using a magic LTV/CAC number as your guide.

After the Board meeting, you go back to your day job and begin revising your operating plan. An LTV/CAC of 3 is good, right? So how will you update the business OKRs to ensure the most time and attention (and $) go to the highest value activities?

Here’s what NOT to do. If you decide your plan is “business as usual,” you should be leading your execution strategy. With my clients, I encourage a deeper analytical dive. You have to run scenarios and stress test your assumptions.

Deconstructing your LTV/CAC Ratio

A crucial part of activating your strategy is continuously analyzing what is working. Every quarter, your team decides when (and where) to accelerate your bets and when (and where) to pull away. Below, I’ve presented a few views from HypoCo (fictional) that demonstrate why drilling past your high-level metrics will help you ask better questions.

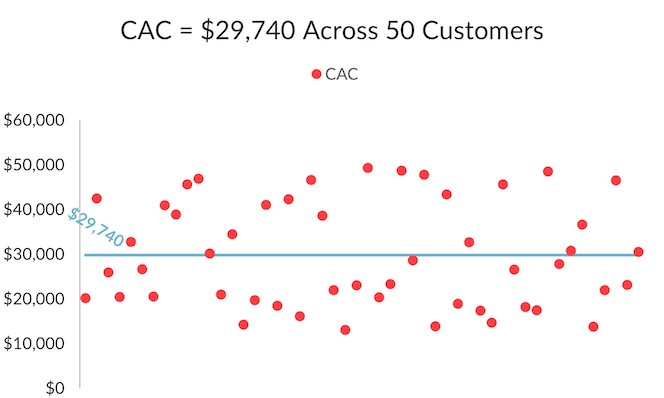

Looking at CAC across HypoCo’s enterprise customer base, we see a high degree of variability. Across 50 customers CAC is $29,470, ranging between $13k to $49k.

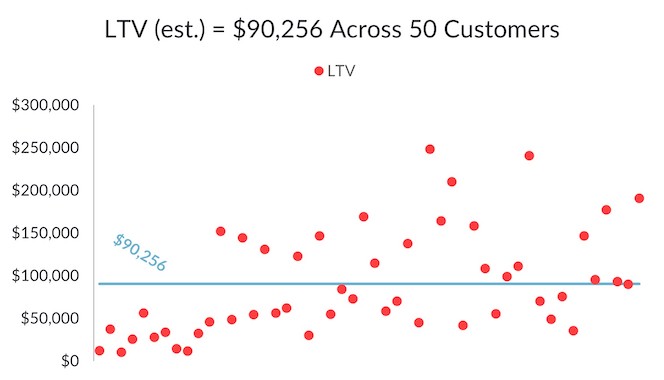

Now, let’s assume we have a crystal ball and we know exactly when customers will leave. I’ve modeled 20% of customers leaving within 2 years, and the top 80% staying between 4 and 10 years. LTV is $90,256, ranging from $10k to $248k

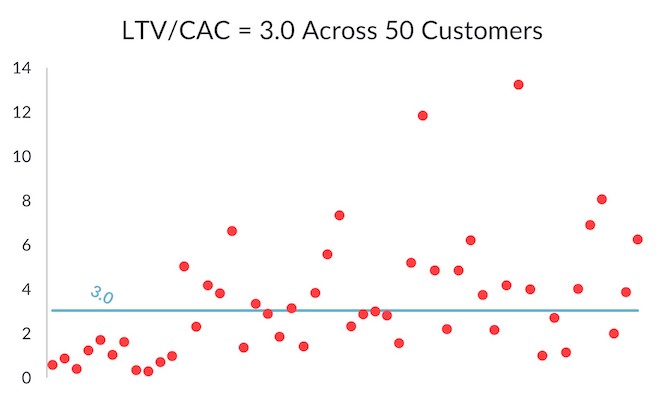

Lastly, let’s look at the resulting calculation of our mystical True North Metric — LTV/CAC. Although our LTV/CAC is 3, roughly 1/3 of the 50 customers fall below 2.5.

By focusing on both OKRs and other metrics, you rarely take a number at face value. Now you can ask more questions in order to focus your priorities for the upcoming quarter.

What Are Your Next Questions

Our first level of analysis provides more (but not sufficient) insight. I would also slice this data several different ways, including a time-based cohort and market segment analysis (e.g. by industry or customer size).

- What drives higher CAC? A change in your SDR org and process? Lower conversions? Longer sales cycles?

- What is your ARR variability? How much is driven by upsell and cross-sell?

- What about retention (both logo and net dollar retention)?

- How is your strategy evolving? If you are pursuing larger enterprise accounts, can you finance the longer sales cycles, higher CACs, and organizational investment? How do you update your hurdle rates and OKRs for a revised operational strategy?

But Everyone Preaches an LTV/CAC Target – What gives?

So why do investors (both venture and public equity investors) like it so much? Two reasons: 1) they can estimate LTV/CAC from financial statements, and 2) they can compare you to a universe, and decide whether to invest. Your job is different — which is, “how can I help my company win?”

And to win, you have to focus on execution. When you set your priorities, you are deciding where to allocate your capital, time, and attention.

If you want to dig into the investing view a bit more, there is a lot of great data and discussion about appropriate LTV/CAC ratios for larger companies (see data from Tomasz Tunguz, Dave Kellogg, and KeyBanc).